by Caroline

Lisa lives in a modernist Eichler house, with glass doors opening from its bright, efficient kitchen to a sunny back yard with citrus trees and a generous picnic bench. I live in a renovated San Francisco Edwardian, with a cork-floored kitchen, a maple island and deep red tile fired in a local pottery studio. My kitchen, with its adjoining family room, is the heart of my home, the center of all our many gatherings, and I expect Lisa feels the same way about hers. So when the opportunity arose to review the new photography collection by Dona Schwartz, In the Kitchen, I jumped at the chance. After all, cookbooks overflow my kitchen bookshelves and spill into the living room; why not add a kitchen coffee table book to the mix?

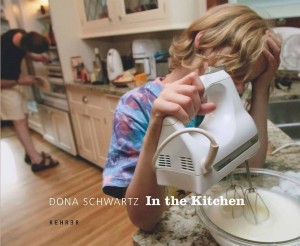

But In the Kitchen, while gorgeous, doesn’t quite fit with the glossy art books. Turning the pages of its color portraits, interspersed with poems by Marion Winik, is like stepping into a documentary film; these are not posed family pictures, nor do they focus exclusively on significant moments in the life of her blended family of eight, which includes her partner, Ken, and their respective three children, ranging in age here from 10 to 21. Instead, Schwartz learned “to create photographs with one hand while wielding a spatula with the other,” and the result is a beautifully intimate portrayal of family life.

The project began on Schwartz’ birthday in 2002, when, with the kids giving her the night off to make a celebration dinner and cake, she found herself at loose ends; her normal role in the kitchen having been happily supplanted by her kids, she decided to get the camera out so that she could still be a part of the action. Schwartz’ professional role as a photographic artist was already firmly established; her earlier books, Waucoma Twilight: Generations of the Farm (Smithsonian Institution Press,1992) and Contesting the Superbowl (Routledge, 1997) are fascinating photographic ethnographies. But turning the camera onto her own family that evening piqued her interest and although, as she says in her introduction, “doing mom work and photographic work at the same time made my life in the kitchen more harried,” she discovers an interesting story unfolding before her eyes: her widowed mother moves close by and becomes a regular fixture in the kitchen (and a reluctant subject in the photos); Schwartz and her boyfriend Ken move in together and blend their families, a move that suspends the photography project for months. “When I next looked through the viewfinder, I confronted a new family,” writes Schwartz, and so “changing my lens to allow for a wider angle of view, the project came to encompass the process of becoming a family, or, more accurately, blending two to become…to become what? (One big happy family? Ken and I were hopeful.)”

She and Ken devise a “blueprint” for their approach to parenting this new family, and family dinner is a key part of bringing the disparate personalities together; they vow to eat dinner together every night, at least during the school week, and then face a new challenge:

“One was a vegetarian, while one cared little for food in general. All took turns as contrarians. One week some of them like red meat, the next week it was anathema to a new subset. Let’s all make pizza! Everyone likes pizza, right? We’d try again. Tastes changed week by week, and forgetting who like what could be unforgivable: ‘You don’t even know what your own kid likes?!’ Trying to find something that everyone would eat was nearly impossible, and even finding a customizable menu was a challenge.”

But they eat. They cook! This book is gorgeous evidence of their cooking. What’s depicted in these pages is not necessarily fancy: eggs are fried, onions sautéed, cookie dough dropped onto sheets. It’s family cooking. One of my favorite pictures shows two brothers, side by side at the stove, holding upended containers — one tin of olive oil, one a bottle of ketchup – over their respective frying pans. On the facing page, the youngest child, Lara, arranges a bright yellow plate with a simple sliced tomato and mozzarella salad while her step-sister, Chelsea, leans against the counter eating a green bean. Another wonderful picture shows two at the stove with spatulas in hand, one sautéing green beans, the other with a tomatoe-y pan of onions, with Eric standing in the background, munching cereal from a box. The image is framed to concentrate our attention entirely on the active elbows and wrists as they stir and snack, the satisfying parallel composition of forearms, skillet handles and spatulas offering a coherent respite in the midst of chaotic family life.

Blending a family can’t be easy — Schwartz admits, “Try as [the kids] might to remove dinner from the list of obligatory rites, Ken and I held fast, and medicated the indigestion our decision often produced”– but there’s a lovely unity in these photographs, a comfortable feeling of togetherness.

Sometimes I wish I could be a fly on the wall and watch my family when I’m not around. I know my presence – even when I’m not directly involved in their activities – affects them, and I’d love that impossible glimpse of them on their own. Looking at Dona Schwartz’ family photos makes me think anew of this problem; she’s not in the images, and so it might be easy to think of the pictures simply as the result of her camera, but they are equally the result of a mother’s sensitive observation. As Alison Nordstrom writes in her preface to the book, “This family is what it is because she is part of it; it may even be what it is because she has photographed it.”

The family — like all families, always in a bit of flux — changed again while the pictures were being taken. Her mother suddenly died (a gathering after her funeral is depicted in these pages, though the only sign of the event is the family’s uncharacteristically dark and formal clothes; captions at the back of book make the occasions clear), and two more kids moved out, joining the two already off at college as occasional visitors home. After two years of pictures, Schwartz writes, “When I looked through the viewfinder there were fewer teenagers and I saw them less often.. . . I came to realize our kitchen moment was passing.”

In the Kitchen offers such a beautiful look at her family’s “kitchen moment,” it makes me grateful that I can expect many more years of my family home and gathered in the kitchen, but also optimistic that even after this intense period of our own kitchen moment has passed, it will occasionally, if temporarily, recur again. As for Schwartz, she writes, “I no longer actively scrutinize or assess, no longer search for clues to emergent identity. I rarely experience the pleasure of framing a telling kitchen-moment I have discovered and rendered visible in a photograph. I now seek these picture pleasures elsewhere. Instead I can often kick back, go with the flow, and watch our family cook.”

all images copyright Dona Schwartz

Foodie McBody

May 31, 2010 @ 11:55 am

This looks wonderful. I definitely want to check it out! I’d love to see the caption of that Coke-bottle photo, LOL.

Caroline

May 31, 2010 @ 5:29 pm

Good point about the captions! I’ve added them now.